Ancient Chronology

More than twenty years ago two

important articles were published in the scientific journal Radiocarbon

(vol. 28, No. 2B, 1986). Both were

authored by Minze Stuiver

of the University of Washington, Seattle and Gordon W. Pearson of Queens

University Belfast, Northern Ireland. The first, entitled “:High-Precision

Calibration of the Radiocarbon Time Scale, AD 1950-500 BC” and the second

“:High-Precision Calibration of the Radiocarbon Time Scale, 500 – 2500 BC” have

helped initiate the science of dendrochronological

dating, in other words the use of carbon 14 dated tree rings, to establish the

archaeological chronology of the Ancient Near East and elsewhere. Radiocarbon ages of dendrochronologically-dated

wood spanning the last 4500 years were measured at both the

A recent paper by Hiroshi Sakurai, Wataru Kato, Yosuke Takahashi, Kayo Suzuki, Suichi Gunji and Fuyuki Tokanai from the Yamagata University Department of Physics

in Japan (entitled, “14C dating of ~2500 Year Old Choukai

Jindai Cedar Tree Rings from Japan Using Highly

Accurate LSC Measurement”, Radiocarbon Vol 48,

No. 3, 2006, pp. 401-408) begins by noting that the standard IntCal04

calibration curve (Reimer et. Al 2004) “shows a flat range of radiocarbon ages

for the 300-yr period between 2670 and 2370 cal BP. Although this is right across the join of the

two data sets mentioned above, Sakurai et al cite the standard explanation that

this is between two remarkable periods of excess changes in carbon14, the

so-called Maunder and Sporer events (M. Stuiver and F. Braziunas, 14C and

Century-scale solar oscillations” Nature 338:405-7 1993). Radiocarbon ages of 8 decadal tree rings and

66 single year tree rings by Sakurai et al using a highly accurate liquid

scintillation counting technique yielded 14C ages between 2757 and 2437 cal BP

with an estimated 95.5 % confidence level.

Between 2580 and 2520 cal BP their ages were about 16 years older on average

than both IntCal04 and QL German oak data sets.

The authors believe that their youngest tested sample, D225, dates

between 500 and 475 BCE. They note that Anatolian wood from the early eighth

century is offset by ~30 14C years from the

In the western world we are used to

the Gregorian calendar and the previous Julian calendar instituted by Julius

Caesar, upon which the Gregorian calendar is based. In 1582, Pope Gregory

XIII ordered the advancement of the Julian calendar by 10 days to

correct errors which had crept in since the Julius Caesar had first introduced

the calendar in 45 BCE. The change was not introduced in

The establishment of chronology is far from definite, even in its

outline. If, for the last Sothic period (from

1321 B.C. to 139 A.D.), the dates confirm one another, everything becomes

topsy-turvy in the preceding ones. A

number of impossibilities point to the fact that certain documents must have

been interpreted erroneously. If the

date on the great Buto Stele is accepted, the ruler

named in the Ebers papyrus cannot possibly be

A major piece of evidence for Sothic

dating calculations is this Ebers papyrus now held in

the University library in Liepzig. It is often interpreted to date from the 9th

year of the reign of Amenhotep I, the second king of

the 18th dynasty. This is because

the name on the papyrus is usually read as Djeserkare. However, as von Bomhard

points out, from a palaeographic point of view, the handwriting appears to

belong to the Middle Kingdom rather than the 18th dynasty and the Hieratic script for the king’s name can be read in more than

one way (p. 41). There is more to

indicate that conventional Egyptian dating is too early.

Meanwhile, if we look at the pottery

records from around the eastern Mediterranean, the recent three volume Timelines

Studies in Honour of Manfred Bietak (Ernst

Czerny, Imgard Hein, Herman Hunger, Dagmar Melman, Angela Schwab,

eds. Orientalia Lovaniensa Analecta 149, 2006) vol. 2, contains the following

statement by Peter M. Warren, who after making a careful study of all the

pertinent Late Classical pottery to look at relations between eastern

Mediterranean civilizations in the Bronze Age, states (p. 319), "We simply

note that the now commonly accepted correlation of LC IA:1 as just pre-New

Kingdom and LC IA:2, including White Slip 1 and the bowl from Thera, as Earliest New Kingdom is completely in accord with

the chronology set out above. In fact a large network of interconnections

locks together the Aegean, Cypriote, Near Eastern and Egyptian chronologies,

with Proto White Slip, White Slip 1 and the Tell el-Daba

and Tell el-Ajjul stratigraphic

sequences at the heart of the network, with White Slip 1 dating from the

beginning of the New Kingdom (1540 BC) and the Theran

eruption at about 1530 BC. Radiocarbon-derived dating, however, placing

the eruption and so the end or near end of LM 1 A at c. 1650 BC, remains

entirely incompatible with the network of dated crosslinks

with the historical chronology of Egypt. Students must assess the

likelihood that this historical chronology at the beginning of the

Much also perhaps depends on the interpretation of ancient words such as the Hebrew shannah and also the ancient Sumerian MU:

In

ancient Sumerian, the phonetic mu logogram MU

is said to mean "name, year, fire, burn" It

is also related to another Sumerian symbol/logogram ![]() mu which means the vowel "a" or the word

"water" and is said to have developed from a cuneiform representation

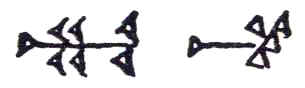

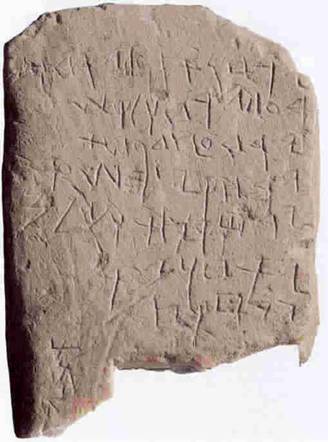

of waves. In early records from tablets discovered at Drehem MU is depicted in cuneiform as shown on

the left. Later in the Assyrian period it is depicted as shown on the

right. Since the cuneiform designs were apparently originally a

development from pictographs, it is interesting to speculate whether the design

is meant to represent the position of the sun at the New Year and even the way

the sun lined up with the gates and entrance to the temple where New Years

festivals were celebrated. Margaret Cool Root (ed.) This Fertile Land

- Signs + Symbols in the Early Arts of Iran and Iraq (

mu which means the vowel "a" or the word

"water" and is said to have developed from a cuneiform representation

of waves. In early records from tablets discovered at Drehem MU is depicted in cuneiform as shown on

the left. Later in the Assyrian period it is depicted as shown on the

right. Since the cuneiform designs were apparently originally a

development from pictographs, it is interesting to speculate whether the design

is meant to represent the position of the sun at the New Year and even the way

the sun lined up with the gates and entrance to the temple where New Years

festivals were celebrated. Margaret Cool Root (ed.) This Fertile Land

- Signs + Symbols in the Early Arts of Iran and Iraq (

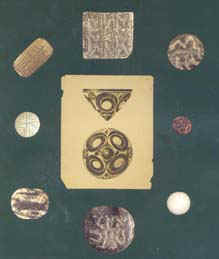

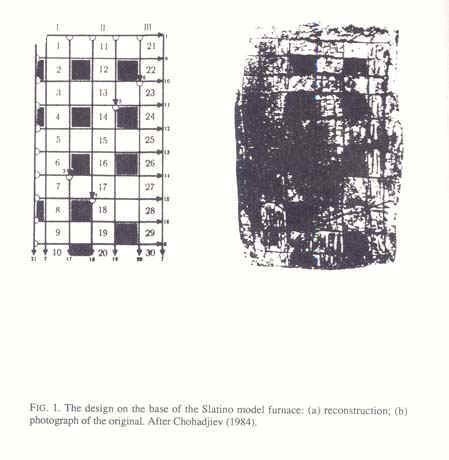

From

earliest times in many prehistoric cultures, the movements of the moon, stars

and planets were used for keeping track of time. Prehistorica

trading patterns show strong possibilities that these methods of measuring time

were not unrelated to other adjacent cultures. Work by a Croatian

archaeologist, Dr. Aleksandar Durman,

in the eastern Croatian town of

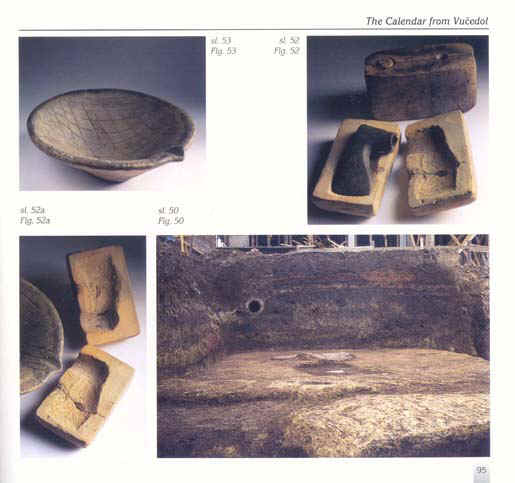

Durman has dedicated years of research to the pot, which was unearthed in 1978

in an ancient copper smelter in Vinkovci. Durman says the earliest calendars appeared around 3000 BC

and that he only recently realised the importance of

the markings on the pot, which dates from the Vucedol

culture around 2600BC. He says the

Durman discovered that the markings on it appeared to be

illustrations of constellations visible in the sky from the 45th parallel.

Durman discovered that the markings on it appeared to be

illustrations of constellations visible in the sky from the 45th parallel.

"Unlike other ancient calendars, usually based on the

movements of the moon or the sun, this is an entirely astral calendar," he

says.

Durman says that on the planes of eastern

He found that each season of the year was represented,

in one of the four strips on the pot, by constellations dominating the sky in

those months. With comparison to the Sumerian, Egyptian, Indian and other

ancient calendars, the constellations were easy to recognise,

Durman says.

The markings confirm that the constellation of Orion

had a special place in the Vucedol people's view of

the world - it essentially heralded the beginning of a new year.

"In the times of the Vucedol

culture, Orion's belt, which is the dominant winter constellation, sank under

the horizon exactly on March 21, thus marking the spring equinox," Durman says.

The characteristic symbols also decorated hundreds of

pieces of pottery of the Vucedol culture - named

after an archeological site near the eastern Croatian town of Vukovar, about 300km east of Zagreb - displayed in an

exhibition in the capital.

The Vucedol culture emerged

around 3000BC on the right bank of the River Danube in eastern

The people of Vucedol were

originally cattle breeders, but with the discovery of copper smelting, their

culture began to flourish and later spread throughout central and southeast

The copper worker was an important figure in this

shamanist culture, as he was regarded as someone who could reach into the womb

of the Earth to take the ore and with his craft interfere in the natural

processes.

"A metallurgist had a role of the shaman and was

considered as having the ability to control the passage of time, and thus the

calendar," Durman says.

The Vucedol people also practised human sacrifice in complicated rituals.

A story of one of these rituals was recorded on a piece

of pottery bearing symbols of Mars, Venus and the constellation of Pleiades.

The piece was discovered in a grave beside skeletons of a man and a woman in Vucedol in 1985.

The bodies, covered with charcoal, were probably

sacrificed after a rare celestial phenomenon involving the passage of Mars and

Venus through the Pleiades, researchers led by Durman

suggest.

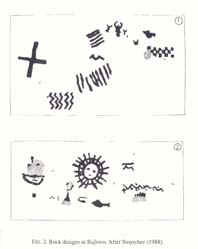

Tsvetanka Radoslavova, in "Astronomical

knowledge in Bulgarian lands during the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age"

(IN Archaeoastronomy in the 1990's - Papers

derived from the third 'Oxford' International Symposium on ?Archaeoastronomy,

St. Andrews, U.K., September 1990, Clive L.N. Ruggles,

ed. (Loughborough: Group Publications Ltd. 1993, pp.

107-116)) gives examples of symbols in the rock designs of Bajlovo,

dated between the third and first millenia BCE

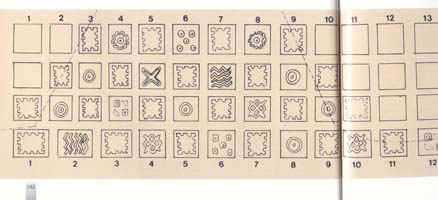

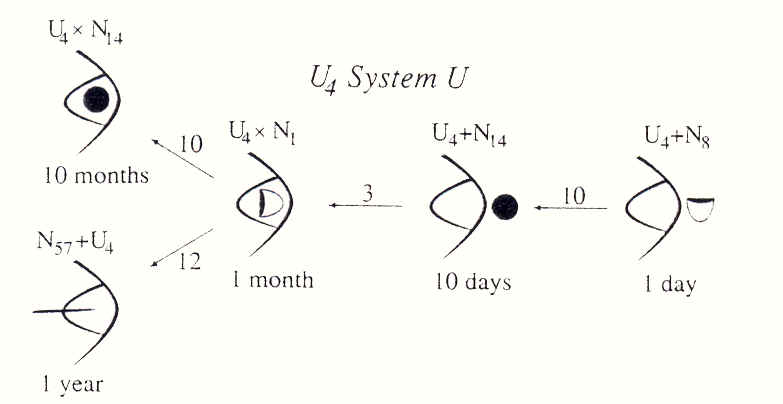

According to Peter Damerow and Robert K. Englund, (Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow and Robert K. Englund, Archaic Bookkeeping – Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East translated by Paul Larsen (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1993) pp. 25ff.), there were at least some sixty proto cuneiform numerical signs (see fig. 27) In contrast to the great majority of ideograms these signs were not incised into the moist surface of a clay tablet. Rather they were impressed with a round stylus held either obliquely or in a vertical position relative to the writing surface. Even now, not all of these symbols are completely understood by modern scholarship. In fact, ten symbols in the list do not belong to any of the systems currently understood by scholars - and these symbols are just from one site, ancient Uruk in the Uruk III period. Could these round indentations relate to the stars and other celestial bodies as mentioned for dots in the signs and symbols studied by Margaret Cool Root? For example, 12 and 10 months are believed to be represented by the U4 system as follows:

Could these proto cuneiform symbols give insights into how time was mentioned in earliest times from a biblical point of view?

Since Rabbinic times and before, the Jewish Anno Mundi calendar has dated the creation of Adam as having taken place in 3760 BCE. However a cursory look at Genesis indicates that dates were likely calculated in a different way in early biblical times. While often ascribed to myth, the dates in Genesis 5 provide an important example:

|

Genesis 5 |

shannahs at son's birth |

shannahs at death |

|

Adam |

130 |

930 |

|

Seth |

105 |

912 |

|

Enosh |

90 |

905 |

|

Kenan |

72 |

910 |

|

Mahalalel |

65 |

895 |

|

Jared |

162 |

962 |

|

Enoch |

65 |

365 |

|

Methuselah |

187 |

969 |

|

Lamech |

182 |

977 |

|

Noah |

500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total shannahs: |

1558 |

7825 |

The

verb form of the Hebrew word shannah also

means "change". Perhaps here in Genesis, it is assumed

astronomical changes that are being noted, rather than specifically

"years" as the word is traditionally translated. For example

Bruce Gardner, argues in his The Genesis Calendar - The Synchronistic

Tradition in Genesis 1-11 (University Press of America 2001) that Enoch's

position as seventh in this list and the number 365 may well be related to the

days of the 365 day calendar, citing Cassuto, Zimmern and Driver's observation that "Enoch may thus

be reasonably regarded as a Hebraized Emmeduranki...

interpreted in a purely ethical sense." (S.R. Driver, The Book of

Genesis (

This day shall be a day of remembrance for you. You shall celebrate it as a festival to the LORD; throughout your generations you shall observe it as a perpetual ordinance.

Fleming notes (p. 48) that the zukru carried special status in the public religious life of Emar and required the sacrifice of 50 calves and 700 lambs, an amount exceeded only by the grand zukru celebrated every seventh year.

It

is, however, important to investigate further this idea that the root of shannah originally meant "change" and

could therefore have been possibly applied to any regular celestial change,

e.g.. "lunar" or "equinox" as well as

"year". (For a general indication of the importance of the ancient

near eastern concept of the "year name" see for example Marc

Van De Mieroop's A History of the Ancient Near

East ca. 3000-323 BC (Blackwell Publishing, 2004) p. 61, Box 4.1) Thus

biblically we have references to the seasons of the year (the spring or fall

equinox): te qûpat hashshanâ "the turning of the year (Exodus 34:22

[fall]: 2 Chronicles 24:23 [spring]), and te shûbat hashshanâ, "the

returning of the year" (2 Samuel 11:l; 1 Kings

Genesis

Genesis 17:1 When Abram was 50

[instead of 99?] years old, the LORD appeared to Abram, and said to him,

"I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless.

Genesis

This would appear to be also

supported by comparisons with the Old Akkadian šanû whose first meaning in the Chicago

Assyrian Dictionary (p.389) is "second (of two or more)" including of

time designations such as "second day" "second time" and ša-ni-tu šattu ina kašâ di "when

the second year [equinox?] arrived." In Mari intercalary

months were called tšnît Month Name. "to

become different, strange, change (said of appearance or location of an

object)" ša kakkabâni

šamâmi man: zâsunu iš-ni-ma "the position of the stars in the sky changed"

It does not seem far fetched that ancient Hebrew usage could have originally

paralleled this.

Stephen

Langdon's Babylonian Menologies and the Semitic Calendars (1935) stated:

The Sumerians divided the twelve lunar months into two parts...

There is consequently a second New Year in the Sumerian and Babylonian

calendars. The custom of beginning the year in the autumn after the feast

of ingathering of the last fruits, the hag ha'asip,

at the end of the year, was the original Hebrew custom[6]....

This is corroborated by Mark Cohen's more recent The Cultic Calendars

of the Ancient Near East, (CDL Press, Bethesda, Maryland, 1993) (see for

example http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/religion/sumerianakitu.htm)

Many years ago, Langdon cited the following seventh century Assyrian

educational text :

59 mit-hur-ti res

satti sa kakkab ÁS-GAN ta-mar-ti d.Sin u

d.Samsi sa arah Adari u arah

Ululi[7]

from which Langdon notes "Here obviously Adar and Elul, 12th and 6th

months indicate the equinoxes." And translates (p. 109):

59. "The harmonizing (epact) at the beginning of the year in Aries,

the rising of the moon and sun in Adar and Elul", ..

The Assyrian word translated as "year" here, satti has been considered an Assyrian equivalent of the Sumerian mu and the expression, res satti is generally translated "new year" which equates to the Hebrew Rosh Hashanah. (Aries appeared at the eastern horizon in mid-September.) A primary meaning of the Assyrian word shanu however is "second" which could apply to the equinoxes.[8] The Assyrian word mû had primary meanings relating to "water".

This can also

be related biblically to the medieval Jewish commentator Ibn

Ezra's statement that the biblical text of Ecclesiastes 1:5-6 should be

translated to describe the movement of the sun along the earth's horizon

between spring and fall equinoxes: "The sun rises and the sun sets,

hastening to its place and rising there. It walks to the south and turns

to the north".

Tablet III of the Gilgamesh epic begins with the following statement in a speech of Gilgamesh to the his mother, the "Lady Wild Cow" goddess (lines III 31-32) according to the translation of Andrew George The Epic of Gilgamesh - The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian (London: Penguin Books, 1999, 2003 rev. ed) p. 24:

"On my return I will celebrate New Year twice over, I will celebrate the festival twice in the year."

According

to George's more academically rigorous The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic - Introduction,

Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts (

"I will return and perform the akitu festival twice in the year / the akitu I will perform twice in the year"

lu-us-sah-ra-am-ma a-ki-tum-ina satti (ma.an.na) 2-su lu-p[u-u]s / lu-pu-us-ma a-ki-tum ina sat-ti 2-su

According

to Fleming (op. cit. p. 134ff) the akitu

festival "remained the supreme calendar event in various southern cities: Uruk (with Anu),

The ages in much of Genesis Chapter 5 make more sense as moons than as our years. The translation of yom at the beginning of Genesis should perhaps also be tied to this sliding scale method of indicating the passage of time. Instead of a literal day, the creation story, perhaps in line with the week long celebration of rosh hashannah was meant symbolically from its inception rather than literally. Thus it is not so far fetched that the Garden of Eden might have been situated in the Early Bronze Age.

Oded Borowski's Agriculture in

Iron Age Israel (

An

important source of help and encouragement on

this investigation of ancient biblical dating has been Professor Emeritus Dr.

Malcolm Horsnell from

"In

ancient

"(i) Each year could be

given a number, such as a regnal year number. Regnal year numbers were used in the Early Dynastic Period

(e.g. at

"A

year-name was a "name" used to identify a year so that one could

refer to a particular year in contrast to another year.".... The

question I asked him when I first met him was whether the Sumerian mu (which also means "water") or the Akkadian limu/limmu is

mistranslated as "year", especially since water comes twice a year -

by spring floods and fall rains... Malcolm did not rule out this

possibility but agreed it warranted further study. This was before I

discovered Daniel Fleming's Time at Emar which

studies a late Bronze Age tablet from Emar whose

calendar went from equinox to equinox as noted above. It thus first

occurred to me that a very large portion of Mesopotamian history could possibly

be half as long as previously thought and much of the early biblical history

might be half as long or even younger as well. I still wonder if there

might be a doubling up of the reigns of more Egyptian dynasties, for example Ramesses II and III. So far in my research it seems

as though most of the known history of Ramesses II

took place in the first twenty years of his reign. Is it so far fetched

that his sons may have co-reigned with him? For example the Journey of Wen-Amon, traditionally dated c. 1100 BCE and the early

21st dynasty depicts a political situation in Egypt where the House of Amon (which John A. Wilson, in his translation, follows

with the expression "Lord of the Thrones" in square brackets,

see James B. Pritchard, referring to the Egyptian god Amon,ed.

The Ancient Near East, vol 1 - An Anthology of

Texts and Pictures (Princeton University Press, 1958, 1973) p. 16) has sent

Wen-Amon to

|

EGYPTIAN DYNASTY 19 (about 1292-1185 BC) |

Traditional length of reign |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

||||

|

|

8 |

||||

|

66 |

|||||

|

|

10 |

||||

|

7 |

|||||

|

3 |

|||||

|

8 |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGYPTIAN

20th DYNASTY 1182-1070 |

|

Traditional

length of reign |

||

|

Setnakhte |

1185-1182 |

|

|

3 |

|

Ramesses III (1182-1151) |

|

31 |

||

|

Ramesses IV (1151-1145) |

|

|

6 |

|

|

Ramesses V (1145-1141) |

|

|

4 |

|

|

Ramesses VI (1141-1133) |

|

|

8 |

|

|

Ramesses VII (1133-1126) |

|

7 |

||

|

Ramesses VIII (1133-1126) |

|

1 |

||

|

Ramesses IX (1126-1108) |

|

18 |

||

|

Ramesses X (1108-1098) |

|

|

10 |

|

|

Ramesses XI (1098-1070) |

|

28 |

||

|

Dynasty 19 High Priests of Amun

in |

|

|

|

|

Dynasty 20 High Priests of Amun

in |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

burial |

|

Appointment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wepwatmose |

Kitchen I p. 326 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bakenkhons B son of Amenemopet |

Kitchen V p 7 ?, 397-399 |

|

|||

|

Nebneteru |

Kitchen I p. 326 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Usimare-nakht |

Kitchen V p 399 |

|

|

||

|

Nebwenenef |

Kitchen III, p. 282-291 |

Tomb 157 |

year 1 |

|

|

|

Ramesses-nakht |

Kitchen V p 399 VI p 87-90, 531 |

|

|

|||

|

Wennufer |

Kitchen III, p. 291-2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Paser |

Kitchen III, p. 292-3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Nesamun |

Kitchen VI p 531 |

|

|

|

||

|

Bakenkhons |

Kitchen III, p. 293-300 |

|

|

|

|

|

Amenhotep |

Kitchen VI p 532-543 |

|

|

|

||

|

Roma-roy |

Kitchen III, p. 300; Kitchen IV p 127-133 |

|

|

|

Ramesses-nakht |

Kitchen VI p 681 |

|

|

|

||||

|

Hori |

Kitchen IV p 377-8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Herihor |

Kitchen VI p 843-848 |

|

|

|

|

|

Minmose |

Kitchen IV p 378 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Piank |

Kitchen VI p 848-849 |

|

|

|

|

Data derived from K.A. Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions - Historical and Biographical Vols I-VI (Oxford:B.H. Blackwell, 1969-83). This work also contains information about Sed festivals, supposedly celebrated on the thirtieth anniversary of a Pharaoh's reign. What is the significance of years outside the thirtieth year. For example for Ramses II, Kitchen lists the following Sed festivals:

First Jubilee, Year 30

Second Jubilee, Years 33, 34

Third Jubilee, Years 36, 37

Fourth Jubilee, Year 40

Fifth Jubilee, Year 42

Sixth Jubilee, Year 45

Seventh and Eighth Jubilees, c. 48-52 (?)

Ninth Jubilee, Year 54

Tenth Jubilee, Year 57

Eleventh Jubilee, Year 60

Twelfth, Thirteenth/Fourteenth(?) Jubilees, Years 63-66 (?)

W. M. Flinders Petrie's Researchs

in Sinai Chapter XII, "The Revision of Chronology"

(complete chapter, pages 163 - 185) stated:

...In connection with the question of the risings of Sirius in their chronological relation, we must also take notice of the great festival of the sed, or ending, which was a royal observance of the first importance. Every one agrees that the sed festival came after a period of 30 years, as it is stated expressly on the Rosetta stone; but whether this refers to a period of the king, or to an absolute fixed period, is a question. There have been three theories about this festival: (1) that it came after 30 years of reign, as it certainly did under Ramessu II; (2) that it came after 30 years of princedom, counting from the time when the king had been appointed crown prince; (3) that it came at fixed intervals of 30 years, or approximately so. If it can be shown to have a connection with fixed intervals, it becomes of some importance in the history and chronology. The entirely exceptional use of this festival at intervals of three years by Ramessu II was only an egotistical freak.

That this festival did not refer to 30 years of the king's reign is clear from the regnal years that are recorded for it; these are 37, 2, 16, 33, 12, and 22; «p.177:» also it occurs in a reign which only lasted 26 years. That it referred to years of princedom seems unlikely, by those years in which it was celebrated. Mentuhotep's feast was in his 2nd year. Hatshepsut (whose festival came about the 40th year of her age) is not likely to have been associated with her father as heir when she was only ten years old, and when he had also a younger son. Akhenaten is not likely to have been associated on the throne as soon as he was born, yet his festival fell about the 30th year of his age. Tut.ankh.amen, who has the reference to "millions of festivals" in his reign, was only 9 years on the throne, and his predecessor only 12 years, so he never saw the 30th year of his princedom. And Ramessu II is known to have been associated with Sety as prince for some years; yet he celebrates his sed in his 30th year.

Is there, then, any reason for associating these festivals with a fixed period? We have seen how important was the observation of Sirius for regulating the year, and how the whole cycle of months shifted round the season, and was connected with the rising of Sirius. If, then, the months were thus linked to a cycle of 1,460 years, what is more likely than that the shifting of each month would be noticed? This was a period of 120 years, in which each month took the place of the previous one. And a festival of 120 years is recognised as having taken place; it was named the henti, and was determined with the hieroglyphs of a road and two suns, suggesting that it belonged to the passage of time. It is impossible to suppose that this could refer to the length of a reign or a princedom. We may reasonably see in this the feast when each first day of a month fell on the heliacal rising of Sirius, at intervals of 120 years.

Can we, then, dissociate a feast of 30 years from that of 120 years? The 120

years is the interval of one month's shift; the 30 years is the interval of one

week's shift. Having a shifting calendar, it would be «p.178:» strange if

no notice was taken of the periods of recurrence in it, and a feast of 120

years and another of 30 years are the natural accompaniments of such a system.

In the great festival of the renewal of a Sothic period in 139 A.D., the signs

of the months are prominent on the coins of

But if this were true we ought to find that the festivals fall at regular intervals of time. There might be small variations, as the four weeks are 28 days and not 30; so there might be times when by keeping to a week-reckoning of intervals of 28 years they mounted up to 112 years instead of 120 for a month. But this would only lead to anticipating the feast by 8 years before it was set right again at a whole month. We will therefore state all the sed festivals that are known, although we have not a sufficiently certain chronology in the earlier period to test their dates.

|

Narmer |

on mace-head |

(Hierakonpolis, i, xxvi, B). |

|

Zer |

seals |

(Royal Tombs, ii, xv, 108, 109). |

|

Den |

ivory tablet, ebony tablet |

(R. T., i, xiv, 12; xv, 16). |

|

" |

seal |

(R.T., ii, xix, 154). |

|

Semerkhet |

crystal and alabaster vases |

(R. T., i, vii, 5-8). |

|

? |

|

— |

|

Qa |

two bowls |

(R.T., i, viii, 6, 7). |

|

" |

Sab.ef, overseer of the sed heb |

(R.T., i, xxx). |

|

Ra.n.user |

temple at Abusir |

(A. Z., xxxvii, taf. 1). |

|

|

|

B.C. |

Cycle. |

|

|

Pepy I |

Magháreh, 37th year. |

4131? |

4121 |

(L., D., ii, 116, a). |

|

" |

Hammamat, 37th year |

" |

" |

(L., D., ii, 115, a, c, e, g). |

|

Mentuhotep II |

Hammamat, 2nd year |

? |

3522? |

(L., D., ii, 149). |

|

Senusert I |

obelisk |

3439-3397 |

3402 |

(L., D., ii, 118, h). |

|

Senusert III |

Semneh |

3339-13 |

3342 |

(L., D., iii, 51). |

|

Amenhotep I |

|

1562-41 |

1552 |

— |

|

Tahutmes I |

|

1541-16 |

1522 |

(L., D., iii, 6). |

|

Hatshepsut |

|

1500 |

1492 |

(L., D., iii, 22). |

|

Tahutmes III |

Bersheh |

1470 |

1462 |

(S., I, ii, 37). |

|

Amenhotep II |

|

1449-23 |

1431 |

(Pr., A.). |

|

Amenhotep III |

Soleb |

1414-1379 |

1401 |

(L., D., iii, 83-8). |

|

Akhenaten |

Amarna |

1372 |

1372 |

(L., D., iii, 100). |

|

Tut.ankh.amen |

Qurneh |

1353-44 |

1342 |

(L., D., iii, 115-8). |

|

Sety I |

|

1326-1300 |

1292 |

(Mar., Ab., i,31) |

|

Ramessu II |

various |

1270 |

1262 |

(B., T., 1128). |

|

«p.179:» |

|

|||

|

Ramessu III |

El Kab |

1202-1171 |

1202 |

(B., T., 1129). |

|

Ramessu IV |

|

1171-1165 |

1172 |

(L., D., iii, 220). |

|

Uasarkon II |

|

857 |

— |

(N., F.H.). |

|

Feast of 12 years, therefore also |

869 |

872 |

— |

|

|

Tarharqa |

|

701-667 |

692 |

(Pr., M., 33). |

|

Nekhthorheb |

|

378-361 |

362 |

(N., B., 57) |

|

Ptolemy I |

Koptos |

304-285 |

302 |

(P., Kop., 19). |

|

(The references above are those used in my Student's History of Egypt.) |

||||

Now there is no difficulty in identifying the positions of these cycle dates

with the sed festivals, remembering that there

cannot be exactitude nearer than three or four years, as that is only a single

day's shift of Sirius' rising; and eight years' anticipation, as in Hatshepsut, Tahutmes III, Sety I, and Ramessu II may

exactly result from reckoning on by weeks of 28 years' shift, instead of 30.

But by these all agreeing together it is more likely that the observations were

made farther south, say at

Now it is very unlikely that these five exact datings should agree so closely to a fixed cycle by mere accident, and that the other cycles should all fall within the required reigns. The probability is that the sed feasts belong to these cycles, as we have seen is suggested by the length of the cycle of 30 years and that of 120 years.

«p.180:» Looking more closely at the designation of the feast, we see that it is often called sep tep sed heb, "occasion, first or chief, of end festival." This has always been supposed to mean the first occasion in the reign; but we see that in the 37th year of Pepy I (which must be his second occurrence of a 30 years' period) he has a sep tep sed heb; and Amenhotep II, who only reigned 26 years, has a sep tep uahem sed heb, "repetition of the chief sed festival," as uahem is used in other cases for the repetition of a sed festival. These examples show that the adjective tep refers to the quality of the occasion, "the chief occasion of a sed festival." The chief occasion of a sed feast was the 120 years' feast on the shift of a whole month. Let us see how this agrees with these sep tep feasts:

|

|

B.C. |

Cycle. |

Sirius rose. |

|

Pepy I |

4131? |

4121 |

Paophi 1. |

|

Mentuhotep II |

? |

? |

? |

|

Senusert I |

3439-3397 |

3402 |

Pharmuthi 1. |

|

Hatshepsut |

1500 |

1492 |

Epiphi 22. |

|

Amenhotep II |

1449-23 |

1432 |

|

|

Repetition of the sep tep, so the sep |

|

||

|

|

tep was in |

1462 |

Mesore 1. |

|

Ramessu III |

1202-1171 |

1202 |

Paophi 1. |

|

Uasarkon II |

857 |

— |

Khoiak 28. |

Thus, by the chronology which we have before reached, five out of six certain dates of chief occasions of the festival were on the first of a month, or just at the close of a month. That of Hatshepsut is the only exception; the lengths of reigns of the XIth dynasty being too uncertain for us to here include Mentuhotep II. If such agreement were mere chance, not more than one in four of such feasts should fall on the beginning of the month; it is thus fair evidence in favour of this meaning of the "chief occasion," when five out of six agree to it. The cause of the exception in the case of Hatshepsut is unknown to us.

By the agreement (within likely variations) of the exactly dated sed festivals with the epochs of a weekly shift «p.181:» of the rising of Sirius, 30 years apart, and by the chief festivals falling usually on the epochs of the monthly shift, we have a strong confirmation of the connection of these festivals with the epochs of the calendar.

Thus we conclude that when the beginning of a month shifted so as to coincide with the observed rising of Sirius before the sun, a chief sed festival was held and when each week, or quarter month, agreed to the rising, there was an ordinary sed festival.

The name of this festival is, however, "the end festival,"

literally "the tail festival"; it commemorated, therefore, the close

of some period, rather than a beginning. Let us look more closely at the nature

of this great feast, a study of which may be seen in MURRAY, Osireion. The principal event in it was the king

sitting in a shrine like a god, and holding in his hands the crook and the

flail of Osiris. He is shown as wrapped in tight

bandages, like the mummified Osiris figures, and

there is nothing but his name to prove that this was not Osiris

himself. Otherwise, he is seated on a throne borne on the shoulders of twelve

priests, exactly like the figures of the gods. In short, it is the apotheosis

of the king during his lifetime. Now, when we see that the king was identified

with Osiris, the god of the dead, the god with whom

every dead person was assimilated, we must regard such a ceremony as being the

ritual equivalent of the king's death. We have the near parallel in the

Ethiopian kingdom, where, as Strabo says, the priests

sometimes sent orders to the king by a messenger, to put an end to his life,

when they appointed another king in his place (Hist.,

xvii, 2, 3). And Diodoros states that this custom was

forcibly abolished as late as the time of Ergamenes,

in the 3rd century B.C. Dr. Frazer has brought together other examples of

this African custom. In Unyoro the king, when ill, is

slain by his wives. In Kibanga the same is done by

the sorcerers. Among the Zulus the king was slain at the first signs of age

coming on. «p.182:» In Sofala the kings, though

they were gods, were always put to death when blemishes or weakness overtook

them. The same custom appeared in early

Another mode of averting the misfortune of having an imperfect divine king

was to renew the king, not only on occasion of his visible defects, but at

stated regular intervals. In Southern

All of these instances given by Dr. Frazer (Golden Bough, i, 218-31) are summed up by him thus: "We must not forget that the king is slain in his character of a god, his death and resurrection, as the only means of perpetuating the divine life unimpaired, being deemed necessary for the salvation of his people and the world."

We see thus how various peoples have slain their divine kings after fixed periods; or have in later times substituted mock ones, who should be slain at appointed times in place of the real king. Such a «p.183:» ceremony was the occasion of a great festival, fixed astronomically, setting aside all the usual affairs of life.

Now let us learn what we can of the Egyptian festival of the sed heb, in view of the festivals which we have been noticing. The essential point was the identification of the king with Osiris, the god of the dead; he was enthroned, holding the crook and the flail, as Osiris, and carried in the shrine on the shoulders of twelve priests, exactly like the figure of a god. The oldest representation of this festival on the mace of Narmer, about 5500 B.C., shows that the Osirified king was seated in a shrine on high, at the top of nine steps. Fan-bearers stood at the side of the shrine. Before the shrine is a figure in a palanquin, which is named in the feast of Ra.n.user as the "royal child." An enclosure of curtains hung on poles surrounds the dancing ground, where three men are shown performing the sacred dance. At one side of this is the procession of the standards, the first of which is the jackal Up-uat, the "opener of ways" for the dead. On the other side of the enclosure of the dancing ground are shown 400,000 oxen, and 1,422,000 goats for the great national feast; and behind the enclosure are 120,000 captives (Hierakonpolis, i, xxvi, B).

The next detail that we find is on the seal of King Zer (5300 B.C.), where the king is shown seated in the Osirian form, with the standard of the jackal-god before him. This jackal is Up-uat, who is described as "He who opens the way when thou advancest towards the under-world." Before him is the ostrich-feather, emblem of lightness or space; this was called "the shed-shed which is in front," and on it the dead king was supposed to ascend into heaven (see SETHE in GARSTANG, Mahasna, p.19). Here, then, the king, identified with Osiris, king of the dead, has before him the jackal-god, who leads the dead, and the ostrich-feather, which symbolizes his reception into the sky.

«p.184:» The next festival that we have represented is that of King Den, in the middle of the Ist dynasty (5330 B.C.). This shows an important part of the ceremony, when, after the king was enthroned as Osiris, and thus ceremonially dead, another king performs the sacred dance in the enclosure before him. This new king turns his back to the Osirian shrine, and is acting without any special veneration of the deified king (Royal Tombs, i, xv, 16). We do not learn any further details from the published fragments of the Abusir sculptures of the festival of Ra.n.user.

There are no more scenes of this festival till we come down to the time of Amenhotep III, who has left a series of scenes at Soleb. There we see that the festival is associated with a period of years, as the king and the great priests approach the shrines of the gods, bearing notched palm-sticks, the emblem of a tally of years (L., D., iii, 84). The ostrich-feather is placed upon a separate standard, and borne before the standard of Up-uat (85). The royal daughters also appear here in the ceremonies (86), as in some other instances.

In the festival of Uasarkon the details are much

fuller (NAVILLE, Festival Hall). We there learn that the king as a god

was joined in his procession by Amen, both gods being similarly carried by

twelve priests. We also see that the festival, though it took place at

On a late coffin with scenes of this festival (A. Z., xxxix, taf. v, vi), we see the king (or his substitute?) dancing before the seated Osiride figures of himself; the three curtains of the dancing ground are still shown behind him. There are also offerings being made to the Osiride king, as to a god. The erection of obelisks is performed by a man, who makes offerings to the sacred bull, entitled, "Great God, Lord of Anu, «p.185:» Khenti.amenti." The royal sons are shown by three figures, who are seated on the ground before "Upuatiu, the king, Commander of earth and heaven."

The details of these festivals thus agree closely with what we should expect in the apotheosis of the king.

The conclusion may be drawn thus. In the savage age of prehistoric times,

the Egyptians, like many other African and Indian peoples, killed their

priest-king at stated intervals, in order that the ruler should, with

unimpaired life and health, be enabled to maintain the kingdom in its highest

condition. The royal daughters were present in order that they might be married

to his successor. The jackal-god went before him, to open the way to the unseen

world; and the ostrich-feather received and bore away the king's soul in the

breeze that blew it out of sight. This was the celebration of the

"end," the sed feast. The king thus

became the dead king, patron of all those who had died in his reign, who were

his subjects here and hereafter. He was thus one with Osiris,

the king of the dead. This fierce custom became changed, as in other lands, by

appointing a deputy-king to die in his stead; which idea survived in the Coptic

Abu Nerûs, with his tall crown of

Such a festival naturally became attached to the recurring one of the weekly shift of the calendar, the close of one period, the beginning of a new age. It was thus regarded not as the death of the king, but as the renewing of his life with powers in this world and the next, an occasion of the greatest rejoicing, and a festival which stamped all the monuments of the year with the memory of its glory.

Cf. "Was the Sed festival periodic in early Egyptian history" by Patrick F. = O'Mara Part 1 - Discussions in Egyptology, Oxford 11, 1988, pp 21-30 Part 2 - Discussions in Egyptology, Oxford 12, 1988, pp 55-62

IV.

Wenamun's complaint to the ruler of Dor

"When

I got up on that morning, I went |1,13 to the place where the chief was. I said to him: 'I was robbed in your harbor

and since you are the ruler of

this land and since |1,14 you are its (investigating) judge--retrieve my money! Indeed, as for the money, it

belongs to Amun-Re, |1,15 King

of Gods, the Lord of those of the Two Lands; it belongs to Smendes, it belongs to Herihor, my lord and <to> other |1,16 great

ones of Egypt . Yours it is. It is for W-r-t, it is for M-k-m-r. It

is |1,17 <for> Zeker-bal, the

ruler of

|

THIRD INTERMEDIATE PERIOD |

|

|

|

|||

|

1069-525 BCE |

co-regent |

|

High Priests of Amun

at |

|||

|

Dynasty 21 (1085-945) : |

|

Herithor |

1080-1074 |

6 |

||

|

Kings at |

|

|

Piankh |

1074-1070 |

4 |

|

|

Smendes |

1069-1043 |

|

26 |

Pinudjem I, |

1070-1032 |

38 |

|

Amenemnisu/Neferkare |

1043-1039 |

|

4 |

Masaharta, |

10054-1046 |

38 |

|

PsusennesI |

1039-991 |

|

48 |

Menkheperre, |

1045-992 |

53 |

|

Amenemope |

993-984 |

|

9 |

Smendes II |

992-990 |

8 |

|

Osorkon the elder |

984-978 |

|

6 |

Pinudjem II |

990-969 |

21 |

|

Siamun |

978-959 |

|

19 |

Psusennes III. |

969-945 |

24 |

|

Psusennes II |

959-945 |

|

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As

James P. Allen notes in his Middle Egyptian - An Introduction to the

Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs (Cambridge University Press, 2000)

p.65f.: "Although Egyptian texts usually referred to the king, during his

life and after his death, by the throne name, Egyptologists use the Son of Re

name instead. Since many kings were named after their fathers or

grandfathers, a dynasty often had several kings with the same Son of Re

name. To distinguish these, Egyptologists number the kings... These

numbers are a modern convention: they were not known by the Egyptians

themselves." Allen notes (p. 31) that the Egyptian king had a dual

nature. When referring to the king's divine power, the word nswt was used, usually translated as

"king". It is the nswt who

issues decrees, appoints officials and represents

You have taken on your form as breath of life

to give it to the noses

life is possible only when you wish it.

You are the one who creates children of children

with your mouth, eyes and hands

The hymn of Ramesses III to Amun-Re does not address the god by name, but begins as follows:

I will begin to say your greatness as lord of the gods

as "ba" with secret faces, great of majesty

who hides his name and conceals his image

whose form was not known at the beginning.

Still further in section G of the Harris Magical Papyrus, which Assman says (p 147) can be dated to the 19th dynasty:

Hail, one who makes himself into millions

whose length and breadth are limitless

power in readiness, who gave birth to himself

uraeus with great flame

great of magic with secret form

secret ba, to whom respect is shown

King Amun-Re (l.p.h.), who came into being himself

Akhty, Horus of the east

the rising one whose radiance illuminates

the light that is more luminous than the gods

You have hidden yourself as Amun the great

you have withdrawn your transformation as the sun disk

Tatenen, who raises himself above the gods

The Old Man forever young, travelling through nhh

Amun, who remains in possession of all things

this god who established the earth by his providence.

The divine name Amun-Re here is not only given the royal title njswt-bjt, but is also written in a cartouche. According to Assman, the earthly king is a manifestation of the divine nature in the world. His counterpart in heaven is the sun: "In Ramesside theology rule by the king belongs to the aspects of the divine nature and must not be reduced either to a mythical primeval kingship or to a purely divine kingship." How do we know that this manifestation of the divine nature was not in fact shared? Could it have been gradually extended to more than one generation of the Ramesses family simultaneously? Could the expression, Old Man forever young, have referred to a governing reality in which power was shared between Ramesses II as the Old Man and some of his prince sons to enable to government to also be "forever young"?

Since the beginnings of Libby's work with Carbon 14 in the late 1940's Egyptian dating and chronology was used as both a yardstick and a corrective for C14 dating. Now radiocarbon dating is connected with dendrochronology - however early dendrochronology also used Egyptian chronology as a means for "matching" tree ring sequences and calibrating C14 dates. Has modern calibration of radiocarbon dates become as certain as its advocates claim? What is the truth about ancient dating...can the truth be truly known? It seems worthwhile to at least re-examine the biblical evidence in the light of modern science in hopes for finding deeper understandings, perhaps on both sides.

- Rev. Jim Collins

Producer

Naklik Productions Inc.

©2007

Last updated